Summary

Map of China

The People’s Republic of China is a unitary republic and one-party dictatorship. Freedom in the World has categorized the country as “not free” since the first survey in 1973 and today ranks among the least free nations.

China's history is marked by repressive dynasties, civil wars and military government, with only a brief period of a fractious democratic republic. Since 1949, the mainland has had a communist dictatorship called the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Starting in 1978, the government opened its economy to allow private property and business as well as global investment and trade. Under these policies, China increased its GDP and improved living standards over time, but much of the population remains poor.

China's history is marked by repressive dynasties, civil wars and military government, with only a brief period of a fractious democratic republic. Since 1949, the mainland has had a communist dictatorship called the People’s Republic of China

The political system is unchanged. The PRC is governed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which monopolizes power over the state, the courts and social and civic structures. As well, party officials direct state-controlled enterprises and large parts of the private economy.

In 1989, mass demonstrations were organized in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square and around the country calling for greater openness and freedom. The protests were the first serious challenge to the communist regime and were brutally suppressed by the military. Since then, any organized dissent has met with police force, imprisonment and other means of repression. In the area of freedom of expression, the government exercises a comprehensive system of control over media, the internet and speech.

The PRC is the world's fourth-largest country in area (9,596,960 square kms.) and the second most populous (1.425 billion people in 2023). There are 56 ethnic groups but the majority Han dominate (92 percent of the population). The Uyghur and Tibetan minorities are severely repressed and both face ethnic and cultural genocide. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects the PRC’s nominal GDP at $18.5 trillion for 2024. It is the world's second-largest economy next to the United States (at $28.7 trillion in projected output). While average income increased in the last decades, wealth is highly concentrated. The IMF ranked China just 68th in projected nominal GDP per capita at $13,136 for 2024.

History

The First Dynasties

China had many monarchical dynasties. Historians date the first Xia dynasty to about 2200 BCE. The Zhou dynasty (1027 to 221 BCE) was the first to claim rule by divine right (the “mandate of heaven”), a doctrine justifying China’s successive rulers over three millennia.

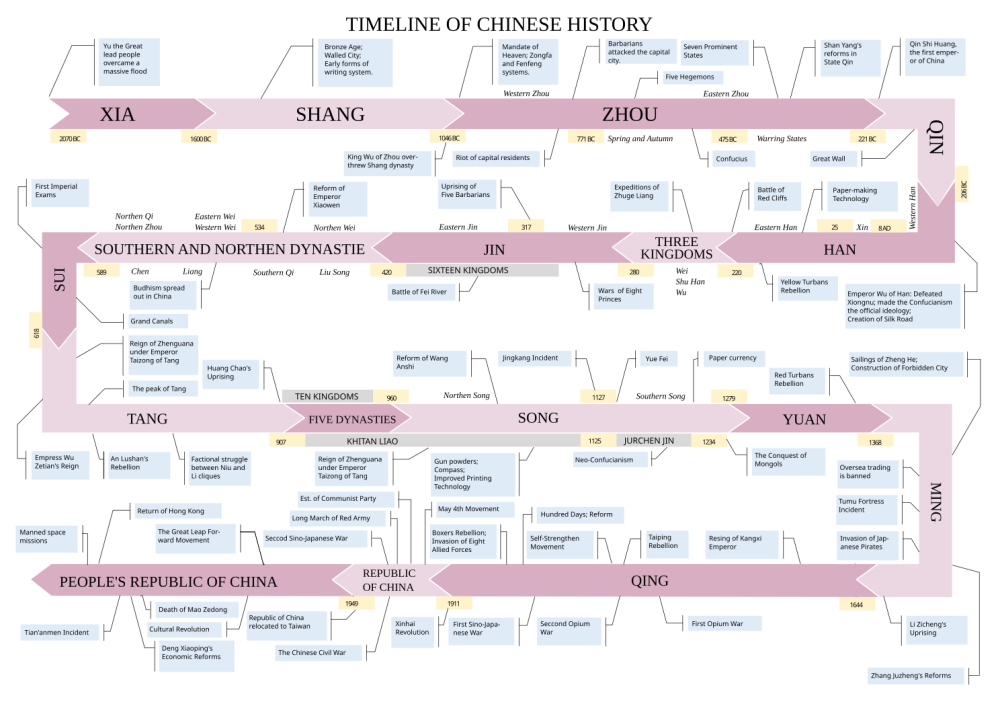

China’s history is marked by repressive dynasties, civil wars and military government, with only a brief period of a democratic republic. Above a timeline, winding back and forth, of China’s governance. Creative Commons. Timeline by Wilfredo Rafael Rodriguez Hernandez.

The Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) . . . introduced Confucianism, an ethical system elevating ideals of unity, knowledge and virtue that served as a religion and state ideology.

The first dynasty to unify the six major warlord powers of the mainland’s early history was the Qin (221–06 BCE). It also first used the term “emperor” for its leader. Although ruling only fifteen years, Qin emperors consolidated a central state by establishing a unified system of weights and measures, a currency, a legal code and the character written language.

The Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE) lasted longer. It introduced Confucianism, an ethical system elevating ideals of unity, knowledge and virtue that served as a religion and state ideology. There were subsequent periods of disunity and warlordism followed by the Sui dynasty (581–618 CE) and Tang dynasty (618–907 CE). The latter presided over what is known as China’s Golden Age.

Foreign Invasions and Later Dynasties

The Song dynasty followed (960-1279 CE), after which there were two foreign invasions, one from Manchuria and the second from Mongolia by Genghis Khan and his descendants. Mongol rule was overthrown by a rebel army led by Zhu Yuanzhang, a peasant who succeeded in consolidating state power. Known as the Hongwu Emperor, he began the Ming dynasty (1368-1644).

Zhu Yuanzhan, depicted above, was known as the Hongwu Emperor, beginning the Ming Dynasty. A peasant, he led a rebel army to overthrow Mongol rule in the 14th century and was emperor for thirty years from 1368 to 1398 CE. Public Domain.

The Ming dynasty adopted neo-Confucianism, an offshoot of Confucianism notable for scholasticism, xenophobia and rigid belief in hierarchy. In seeming contradiction, Ming emperors broke up China’s large feudal estates, banned slavery and encouraged private land ownership. Small agricultural communities became the main producer of food. Ming rulers also developed new industries such as porcelain and textiles and completed The Great Wall, which had been started in the previous millennium by the Qin dynasty.

A second Manchurian invasion introduced China’s final ruling dynasty, the Qing, lasting from 1636 to 1912 CE. The emperors imposed heavy-handed foreign administration. Only Manchus could serve in the administration or army. The identity of ethnic Han, China’s dominant ethnic group, was repressed. Officials enforced a distinctive Manchu hairstyle for males (a shaved head in front with a long ponytail tied in the back) and Manchu dress (considered today traditional Chinese clothing). In other ways, the Manchu ruled similarly to previous dynasties and adopted rigid neo-Confucian norms.

The End of Imperial Rule and the Republic of China

A second Manchurian invasion introduced China’s final ruling dynasty, the Qing, lasting from 1636 to 1912 CE. The emperors imposed heavy-handed foreign administration.

In the 19th century, European powers used superior armaments to force China to trade with the West, especially for opium. Great Britain’s defeat of China in the First Opium War (1839–42) resulted in the British gaining special trade privileges and an open lease of the island territory of Hong Kong that lasted until 1997 (see below).

In 1850, a peasant revolt erupted, in part against Manchu rule and in part against the Qing emperor’s capitulation to the British. Known as the Taiping Rebellion, its citizens’ army gained control of a substantial portion of southern China until it was put down by the Imperial Army with the aid of British and French forces. Over fourteen years, the Taiping Rebellion and its suppression saw tremendous loss of life: 20-30 million people died from revolutionary violence, armed conflict and famine.

The Empress Dowager Cixi seized effective control of the state in the late Qing dynasty and even placed the emperor (known as the Guangxu Emperor) under house arrest in 1896. She backed what was called the “Hundred Reforms” movement but without responding to greater unrest. In 1900, she then backed the radical Boxer Rebellion against foreign dominance. It was put down by an Eight-Nation Alliance that weakened imperial rule further.

The Republic of China was inaugurated on January 1, 1912 [and] the abdication of the newly installed six-year-old Emperor Puyi . . . put an end to 3000 years of formal imperial rule.

A national movement arose inspired by the revolutionary ideas and writings of Sun Yat-sen and others. His Three Principles of nationalism, republicanism and people’s welfare gained a wide following. An uprising in 1911 sparked in a regional capital (the Wuhang Uprising) spread throughout the country. Rival authorities were established, but delegates from provisional assemblies held across China met in Nanjing to establish a new national government. The Republic of China was inaugurated on January 1, 1912.

Sun Yat-sen, who was elected president, negotiated with the reformist head of the Imperial Army, Yuan Shikai, for the abdication of the newly installed six-year-old Emperor Puyi. His abdication put an end to 3000 years of formal imperial rule. To achieve a united national government, however, Sun Yat-sen agreed to cede the presidency to Yuan Shikai.

This fateful move led to the collapse of the central government. Yuan abolished the nascent national assembly elected in 1913 — mainland China's first and only free national election in its history. Yuan moved the capital back to imperial Beijing. He declared himself emperor and attempted to create a new dynasty, whereupon he was forced from power in 1915 by popular protest and rival generals. Central administration broke down, beginning a period of division among leaders of political factions of the army that competed for authority and acted as warlords over territory.

The United Fronts and the Long March

Sun Yat-sen united several republican movements into the Kuomintang (Nationalist) Party. Its military forces gained control of a large part of the south to establish a government. Sun Yat-sen still hoped to reunify China. To do so, he formed a United Front in 1921 with the newly formed Chinese Communist Party (CCP), inspired by its Russian counterpart.

In 1934, facing imminent defeat . . . Mao ordered his Red Army on a long circuitous retreat to the north to escape Chiang’s Nationalist Army. A majority of the communist rebels died along the way, but The Long March, over a total of 6,000 miles, is credited with saving the guerilla army.

After Sun Yat-sen died in 1925, Chiang Kai-shek emerged as the dominant figure among competing generals within the Kuomintang. In 1926, he was named commander-in-chief of the National Revolutionary Army (NRA). Beginning in 1927, Chiang carried out ruthless purges of communists while also sidelining other competitors within the Kuomintang. He re-formed the Republic of China’s central government in 1928 in the city of Nanjing and then launched military efforts to unify China against northern “warlords.”

Chiang renounced the United Front and initiated a civil war to defeat peasant revolts and, in turn, the Chinese Soviet Republic (CSR). The CSR was established by Communist Party leader Mao Zedong in 1931 in discontinuous territories. In 1934, facing imminent defeat in the Soviet Republic’s stronghold in the south, Mao ordered his Red Army on a long circuitous retreat to the north to escape Chiang’s Nationalist Army. A majority of the communist rebels died along the way, but The Long March, over a total of 6,000 miles, is credited with saving the guerilla army.

Japanese Invasion and Civil War

Chiang Kai-shek, who emerged as the dominant figure among competing generals following the death of Sun Yat-sen to lead the Nationalist Revolutionary Army, was Time’s Man of the Year in 1927. Public Domain.

Taking advantage of the outbreak of civil war, the Japanese Empire invaded the northeast region of Manchuria in September 1931. Chiang Kai-Shek, however, sought defeat of Mao’s Red Army before concentrating forces against the Japanese. As China faced the prospect of full-scale invasion, two of Chiang’s own generals in the north kidnapped him in late 1936 to force him to end the civil war and form a Second United Front with Mao’s Red Army against the Japanese. The Japanese army invaded in July 1937 to begin the Second Sino-Japanese War.

The Second United Front broke down as early as 1941, but it allowed communist guerilla forces to regain strength and assert control over parts of China, especially Manchuria and the north. The final defeat of Japan in 1945 did not lead to peace. Civil war soon broke out again between the two sides.

[T]he Red Army . . . progressively gained control over the mainland. Nationalist . . . forces retreated to the island of Taiwan . . . Chiang Kai-Shek declared a new government on Taiwan as the legal continuation of the Republic of China (ROC). Soon afterwards, Mao Zedong declared the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) on October 1, 1949.

Aided now by the Soviet Union, the Red Army (also called the People's Liberation Army) progressively gained control over the mainland. Nationalist (Kuomintang) forces retreated to the island of Taiwan. Previously autonomous, it had recently come under mainland administration. Chiang Kai-Shek declared a new government on Taiwan as the legal continuation of the Republic of China (ROC). Soon afterwards, Mao Zedong declared the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) on October 1, 1949, supplanting any ROC authority over the mainland. Armed hostilities ended in 1950, but technically the PRC remains at war with the ROC and Taiwan is considered part of one China.

Taiwan had a three-decade period of harsh military dictatorship but emerged in the 1990s as a stable multiparty democracy with a successful free-market economy. The constitution still asserts the continuity of the Republic of China, but governing authority is only exercised over ROC citizens on Taiwan. Leaders have not declared independence to avoid direct conflict with the PRC, but the ruling Democratic Progressive Party asserts Taiwan’s de facto sovereignty. It has won presidential and parliamentary elections in the last three elections, the latest in January 2024 (see also Current Issues).

People’s Republic of China

Since being established in 1949, the People's Republic of China has been ruled by a one-party dictatorship.

The constitution, like that in the Soviet Union, established the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as the supreme authority of the state. Mao Zedong, acting as chairman of the party’s Central Executive Committee, exercised full political power. After pronouncing the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949, Mao also had himself appointed the state’s chairman, or president, and named head of the government’s Central Military Commission, a troika of positions that made him paramount leader.

Under Mao’s direction, the PRC developed a variant of communism called “Marxism-Leninism-Maoism.” This ideological doctrine expanded the Soviet Union’s imposition of a “dictatorship of the proletariat” to that of a “dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry.”

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) established a totalitarian system modeled on the Soviet Union. Mao Zedong, the PRC’s paramount leader, signed a Sino-Soviet Friendship Treaty with Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin, in 1950, as commemorated in this stamp. Public Domain.

The totalitarian system that was established was the same as in the USSR, which had provided the People’s Liberation Army key assistance during the Civil War and afterwards. As in the Soviet Union, the Chinese communist system operated according to the Leninist principle of “vanguardism,” which dictates that state power is centralized in the leadership of a revolutionary communist party.

Ideological Campaigns & the “Great Leap Forward”

As paramount leader, Mao Zedong consolidated power through ruthless ideological campaigns carried out by state security organs to repress political opposition. The campaigns had the purpose of eradicating warlords, landlords, other property owners, Nationalists, social democrats and any critics of the CCP among workers and farmers. In each campaign, hundreds of thousands of people were rounded up at a time and imprisoned in a penal and labor camp system that came to be known as Laogai (similar to the USSR’s GULAG). Many political opponents, however, were simply taken to tall buildings and given a choice: jump or be pushed to their deaths.

As paramount leader, Mao Zedong consolidated power through ruthless ideological campaigns carried out by state security organs to repress political opposition.

In 1956, Mao introduced the “Hundred Flowers” campaign. Ostensibly, it solicited suggestions for “rectifying” mistakes in the party-state’s leadership. The campaign to “let a hundred flowers bloom” became a mass movement to express opposition to the CCP’s rule. In response, Mao ordered a new Anti-Rightist crackdown. Millions of people whose critiques had been solicited were dismissed from their jobs, imprisoned or executed.

In 1958, impatient at the pace of socialist development, Mao ordered the Great Leap Forward to fully collectivize agriculture and industrialize the country. Forced collectivization proved disastrous. Agricultural output plummeted. A top government official later admitted that 20 million people died from the resulting famine. (Some demographic experts put the figure at 45 million.)

The Cultural Revolution

The Great Leap Forward was ended in 1963 by the Standing Committee of the Politburo, the Chinese Communist Party’s highest leadership body, which decided to curtail Mao Zedong's powers. It is the only instance a paramount leader’s power was curtailed. Liu Shaoqi replaced Mao as state president and Deng Xiaoping became party general secretary. Mao, however, retained great authority. He responded to these moves by calling for a Cultural Revolution.

In a speech in May 1966, Mao called for the “eradication of the Four Olds” in religion, education, culture and within Communist institutions. (The four were “old customs, old culture, old habits and old ideas.”) His speech set off a revolutionary fervor among Mao loyalists that led to purges of competing factions. Red Guards and student paramilitary groups rampaged through cities destroying any manifestation of “the four olds.” Millions of people were expelled from government institutions. Many were marched to prison or to farm collectives following extra-judicial trials carried out by the Red Guards.

By the end of the year, Liu Shaoqi was arrested and Deng Xiaoping was sent to a collective farm. Mao resumed his role as paramount leader and the Cultural Revolution continued until his death in September 1976. Shortly thereafter, other party leaders re-asserted their power and ordered the arrest of the so-called Gang of Four, led by Jiang Qing, Mao's fourth wife. In official history, the period’s “excesses” are blamed on the Gang of Four, not Mao.

Economic Reforms & Their Results

Deng Xiaoping returned from the work collective in the early 1970s after being rehabilitated by his longtime mentor, Zhou Enlai. Zhou was Mao’s “No. 2,” serving as premier, or head of government, from 1954 until his own death in January 1976. With the two leading figures of the Communist Party and state gone, Deng maneuvered to exert control over party and state policy.

Deng Xiaoping established himself as paramount leader by assuming the same troika of party and state positions as Mao. He then set out to modernize China, changing the PRC’s economic course. In 1978, he introduced what he called the “Four Modernizations.”

Pushing out Mao’s designated successor, Deng Xiaoping established himself as paramount leader by assuming the same troika of party and state positions as Mao. He then set out to modernize China, changing the PRC’s economic course. In 1978, he introduced what he called the “Four Modernizations,” a set of economic reforms in agriculture, industry, national defense and science and technology. The reforms introduced a hybrid communist-capitalist economy encouraging foreign investment and private business alongside state-run conglomerates.

China’s economy boomed over the next five decades. To achieve such growth, the government moved a total of more than 250 million peasants to newly constructed cities for manufacturing job — the largest social engineering project in history. Part of China's “economic miracle” was based on low labor costs and the suppression of worker rights. Spontaneous labor unrest has driven some wages higher, but not to any comparable scale with US or European countries (see also China Country Study in Freedom of Association).

From Democracy Wall to Charter ’08

Several movements for political reform have arisen since the “Four Modernizations” was launched. But Deng Xiaoping and later leaders have made clear: the Communist Party of China (CCP) will not ease its grip on state power.

Several movements for political reform have arisen since the “Four Modernizations” was launched. But Deng Xiaoping and later leaders have made clear: the Communist Party of China will not ease its grip on state power.

Initially, censorship was loosened after Deng’s “Four Modernizations” speech. Activists quickly put up large character banners, a practice from the late imperial period, with news and opinion. The banners were put up along a street in Beijing that became known as Democracy Wall. The most famous was by Wei Jingsheng, an electrician who wrote that democracy was an indispensable “Fifth Modernization.” The banners were soon taken down. Along with other activists, Wei was arrested. He spent a total of eighteen years in prison before being forcibly exiled in 1997. Yet, Wei’s “Fifth Modernization” remains a touchstone for democracy and human rights advocates (see Resources for the text and a review of Wei’s memoirs).

In 1989, the year of democratic revolutions in Eastern Europe, there was a larger challenge to Chinese Communist Party rule. Student protests broke out in the spring in Tiananmen Square to demand political reforms. The demonstrations grew in size and scope across the country. Martial law was declared on May 20, but the protests only increased to include hundreds of thousands of people in Beijing and millions in cities nationwide.

In 1989, the year of democratic revolutions in Eastern Europe, there was a larger challenge to Chinese Communist Party rule. Student protests broke out in the spring in Tiananmen Square to demand political reforms.

Although government officials negotiated with student representatives, the challenge to absolute communist rule was soon ended. On June 4, Deng Xiaoping ordered the army to fire on the demonstrators in Tiananmen Square. Several thousand people were killed or wounded. After the massacre, tens of thousands were rounded up and imprisoned nationwide. Many more were expelled from universities and other state institutions. Officials who had negotiated with the students were purged from state and party positions.

All the tools of a police state were then used to prevent any recurrence of the Tiananmen Square protest, including a censorship ban on any references to it. Arrest sweeps prevented any commemorations, except in Hong Kong (see below.

Even so, a dissident movement emerged similar to what arose earlier in Soviet Bloc communist regimes. In 2008, leading dissidents launched Charter ’08 modeled on a human rights group in Czechoslovakia (it was called Charter ‘77). Appealing for democratic reform, Charter ’08 gained 1,300 signatures before government censors banned it from the internet. The leaders and many signatories were arrested. Charter ‘08’s author, Liu Xiaobo, was sentenced to 11 years' imprisonment. Awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, he could not receive it and died of liver cancer in 2017, still in prison (see Resources).

A Most Stable Dictatorship

Deng Xiaoping, shown above in 1979 on a US trip, became paramount leader of China soon after the death of Mao Zedong. His “Four Modernizations” introduced market reforms while maintaining central communist party political control. Public Domain.

Fearing the type of political and state collapse that occurred in the Soviet Bloc and Soviet Union in 1989-1991, communist leaders rejected any political reforms and kept tight hold on power.

Since Deng Xiaoping’s retirement from key state and party posts in 1992, there have been three successful transfers of leadership. The third transfer took place in 2012, when Xi Jinping, the son of a leading figure from the revolutionary era, assumed the role of paramount leader.

As Mao and his three predecessors did, Xi consolidated power by combining the posts of General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, state president and chairman of the Central Military Commission. Xi cemented his control through an “anti-corruption” campaign that resulted in removal of 400,000 officials, with many sentenced to prison. These included top party figures considered potential rivals.

Fearing the type of political and state collapse that occurred in the Soviet Bloc and Soviet Union in 1989-1991, communist leaders rejected any political reforms and kept tight hold on power.

Unlike Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, his two immediate predecessors, Xi broke an informal agreement established within the central party leadership during Deng’s rule to limit the paramount leader to two five-year terms in his posts. Xi had himself re-appointed to all three leadership posts in 2022-23, asserting a level of control over state power not seen since Mao (see Current Issues).

Suppression of Autonomous Regions

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) asserts dominant power in suppressing minority rights and autonomous regions. One region, Tibet, had established independence from China in 1913. A devout Buddhist society, Tibetans were governed by a religious leader, the Dalai Lama. In 1951, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) invaded Tibet and Chinese security forces brutally repressed Tibet’s Buddhist culture and society. The Dalai Lama and many of his followers fled to India.

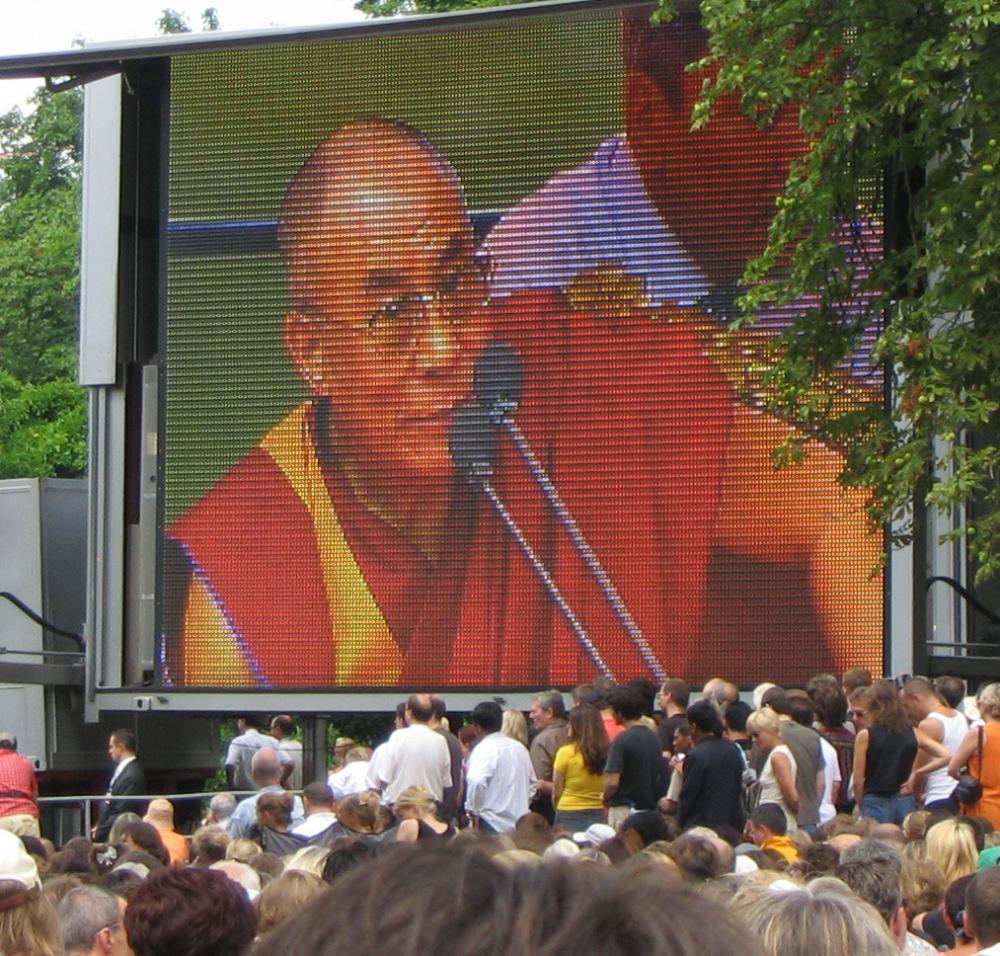

China reoccupied Tibet in 1951 and brutally repressed its Buddhist culture and society. Tibet’s leader, the Dalai Lama, went into exile to direct non-violent resistance to regain autonomy but without success. Shown above at a public event in 2005 in Germany. Creative Commons. Photo by Björn Appel.

The Dalai Lama directed non-violent resistance and called for negotiations with the Chinese government (he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989). To get awarded the 2008 Olympics, Chinese authorities agreed to talks with the Dalai Lama’s representatives, but had no real negotiations for autonomy. Instead, Chinese authorities continued to use modernization projects to destroy Buddhist historical and cultural sites.

In one protest in 2011, 300 Buddhist monks sought to draw world attention to the destruction of Tibetan culture through a desperate campaign of public self-immolations.

Tibetans continued to resist Chinese rule. In one protest in 2011, 300 Buddhist monks sought to draw world attention to the destruction of Tibetan culture through a desperate campaign of public self-immolations.

A second region, officially called the Autonomous Xinjiang Uyghur Region, is in northeast China and home to a Turkic ethnic group, Uyghurs, adhering to Islam. Uyghurs resisted Chinese administrative control for decades only to suffer similar repression as Tibetans. Tensions rose as state-directed Han immigration into the region increased. After a protest in 2009 against the displacement of Uyghur workers, one thousand Uyghurs were arrested and dozens were sentenced to prison or the death penalty. Xinjiang was then put under heavy security control. Repression of Uyghur culture and language heightened. In 2017, the central government began a more systematic policy to eradicate both Uyghur and Tibetan identity (see Current Issues).

Hong Kong: No Longer a Haven

A third territory, Hong Kong, was a former British colony returned to the People’s Republic of China in 1997 after the end of a ninety-nine year lease granted by one of the last Qing emperors (see above). Under a formal agreement the Chinese government made with the United Kingdom, Hong Kong would be governed according to its own Basic Law, or constitution, for 50 years that protected Hong Kong's traditions and laws — a policy called “one country, two systems.” During negotiations between Britain and the PRC, a civic and political movement arose to enhance Hong Kong’s freedoms and rule of law practiced under colonial rule. Since 1997, that movement struggled against encroaching control by Beijing’s authorities.

In 2003, a half million citizens demonstrated against a proposed anti-subversion law that was withdrawn as a result of the protest. In 2012, authorities withdrew a new “national education” curriculum based on Chinese Communist Party orthodoxy due to similar protest. Annually on June 4, a commemoration of victims of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre was organized by the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China spearheaded by teacher union leader Szeto Wah. In 2014, the 25th anniversary of the crackdown, 150,000 people gathered in a candlelight vigil in defiance of threats by Chinese authorities.

Democracy leaders continued their campaign against encroachments on Hong Kong’s freedoms. In 2019, however, massive protests against a proposed new National Security Law led to a more severe crackdown

Soon afterwards, a movement called Occupy Central with Love and Peace organized an informal public referendum on choosing China’s chief executive through direct election and increasing the number of seats in the Legislative Council to direct vote. The government, directed by Beijing, rejected such changes and proceeded to assert greater control over the territory. This sparked a months-long protest movement in central Hong Kong called the Umbrella Revolution because protesters used umbrellas to ward off the spray of water cannons. The protests dissipated under sustained police repression.

Democracy leaders continued their campaign against encroachments on Hong Kong’s freedoms. In 2019, however, massive protests against a proposed new National Security Law led to a more severe crackdown (see Current Issues).

Freedom of Expression

As related in History, the state imposed strict doctrines controlling speech during China’s long period of dynastic rule. There was a brief period of greater freedom at the end of the Chinese empire and the establishment of the Republic of China. But it did not survive the civil war and foreign invasion by Japan that followed. The establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 then brought totalitarian control over all expression, especially during the Cultural Revolution. Slightly less rigid controls were put in place following Mao Zedong’s death but a regime of total censorship remained.

The establishment of the People’s Republic of China . . . in 1949 . . . brought totalitarian control over all expression, especially during the Cultural Revolution. Slightly less rigid controls were put in place following Mao Zedong’s death but a regime of total censorship remained.

Since 2012, under Xi Jinping’s leadership, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has tightened state-party control over the media, the internet and speech. Internet and wireless communication did allow for some free speech through blogs and social media, but digital expression is now tightly restricted by China’s “Great Firewall.” This is a vast state apparatus monitoring and controlling access to information and any open communication (see below). A more detailed description of freedom of expression in China’s different epochs follows.

Imperial China and the Republic

Exile publications distributed within China broke through imperial censorship, allowing Sun Yat-Sen to gain greater following for his republican ideas. Above, a 1904 article published in the Hawaiian Chinese News by Sun Yat-sen denouncing the monarchist press. Public Domain.

From the outset, emperors and territorial warlords imposed rigid systems of control over expression that rewarded obedience and repressed dissent. Not surprisingly, Chinese emperors established a formal list of censored books as soon as mass book production was introduced. Under the later Ming and Qing dynasties, neo-Confucian doctrines stressed loyalty and submission to central authority. Free thought and inquiry were discouraged.

In the late imperial period at the end of the 19th century, there was more intellectual and political ferment. This was sparked especially by exiles living in Japan, Southeast Asia and the United States. Newspapers produced in these communities were circulated within China. Émigrés such as Sun Yat-sen, who studied in British-run schools in Honolulu and Hong Kong, were influenced by liberal ideas. Wider distribution of Sun Yat-Sen’s publications gained adherents to his “Three Principles” ideology of nationalism, republicanism and people's welfare.

Sun’s followers organized a national movement aimed at overcoming imperial rule. Following the Wuhang Rebellion in 1911, a national meeting of delegates elected in provincial assemblies met the next year to establish the Republic of China (ROC). There emerged much greater freedom of expression but it did not take deep root. After Sun’s death in 1925, democratic hopes were dashed by Chiang Kai-shek’s greater authoritarian rule, as well as by the civil war and foreign invasion (see also History above).

The People's Republic of China

When Communist Party of China (CCP) seized power of the mainland in 1949, it ended all forms of intellectual freedom and imposed a single ideology, communism, or more specifically “Marxism-Leninism-Maoism,” which governed all aspects of life.

When Communist Party of China (CCP) seized power of the mainland in 1949, it ended all forms of intellectual freedom and imposed a single ideology, communism, which governed all aspects of life.

The civil society that had developed during the previous century was wiped out. All media and publishing of books and newspapers became controlled by the state. Strict censorship was introduced and state-directed ideological campaigns enforced political uniformity in both public and private speech. Deviation from the communist line was repressed.

Beginning in the mid-1960s, the Cultural Revolution brought a new level of terror to enforce communist doctrine. While Deng Xiaoping’s reforms and their allowance of private business marked an economic departure from communist orthodoxy, the regime continued to clamp down on free expression initiatives such as the Democracy Wall movement and to suppress any political protest movements like the Tiananmen Square uprising and Charter ’08 (see also History above).

Media Control and Censorship

Still, the period of economic reforms brought an increase in commercialized print and broadcast media. There are now more than 2,000 newspapers, 7,000 magazines and journals and 1,000 radio and 3,700 television stations. However, commercialization did not mean less state control. Any “private” media had to have majority state or communist party ownership. Any local station had to broadcast the news shows of the one national television broadcaster, the state-run China Central Television (CCTV).

All state and nominally private media are supervised by the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department, which has branches at all levels of territorial administration. . . Once appointed, editors and journalists attend “ideology reinforcement conferences” to be schooled in censorship.

All state and nominally private media are supervised by the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department, which has branches at all levels of territorial administration. Appointments of editors, broadcasters and senior journalists are made under the party's patronage system. Once appointed, editors and journalists attend “ideology reinforcement conferences” to be schooled in censorship. As Xi Jinping made clear in a 2016 speech reported in The New York Times, all journalists “must serve the party” (see Resources).

The realm of taboo topics is enormous. Among them are: questioning the CCP’s political monopoly; negative portrayals of PRC or CCP leaders; the existence of censorship itself; the Tiananmen Square massacre; dissidents or banned spiritual movements like Falun Gong; and Uyghuristan or Tibet.

All media must comply with “propaganda circulars.” These are issued multiple times a day by the Central Propaganda Department and its local branches. These direct what propaganda must be included and what news must be excluded in broadcasts and newspapers. Editors and journalists who dare to report on local corruption are often punished with dismissal or arrest.

The ”Great Firewall”

The internet has grown to have now 1 billion users. As internet use grew, this initially led to some diversity in expression. But all use of the World Wide Web, email and social media have now become fully monitored by the state’s “Great Firewall.” This is a vast censorship apparatus controlling what sites may be accessed as well as what may be posted. In 2013, there was reported to be 2 million monitors; their number has certainly grown.

[All] use of the World Wide Web, email and social media use have now become fully monitored by the state’s “Great Firewall.” This is a vast censorship apparatus controlling what sites may be accessed as well as what may be posted. In 2013, there was reported to be 2 million monitors; their number has certainly grown.

Websites deemed politically or socially dangerous are not accessible to Chinese users. There are filters for foreign media, foreign social media and blogging sites. Meanwhile, parallel Chinese social media sites for blogging and instant messaging are strongly encouraged for use. (On internet controls, see Economist and New York Times articles as well as Freedom of the Net in Resources.) In addition, the government actively influences the public through social media posts and “trolling.” One report in 2017 estimated up to 486 million posts put up each day by government-controlled accounts.

Web users do get around restrictions to access and disseminate information and express non-official views. The size of this independently minded web community is indicated by mass campaigns around public disasters. By posting unofficial pictures and accounts before censors have a chance to control reporting, micro-bloggers have forced authorities to provide more transparent news coverage of events. Such campaigns even affect public policy, such as changes to development plans endangering the environment.

Testing Limits Increases Repression

In general, though, testing the limits of expression is repressed. In January 2013, for example, journalists at the Guangzhou-based Southern Weekly went on strike after censorship officials changed an editorial urging greater adherence to China’s constitution. The censors blocked the editorial for supposedly supporting the charter of the New Citizens’ Movement, an informal network of individuals calling for greater adherence to stated (but ignored) human rights guarantees in the constitution.

The New Citizens’ Movement arose in 2012 sparked by an article by lawyer Xu Zhiyong urging adherence to civil rights provisions in the Chinese Constitution. He was quickly arrested. Above, a demonstration calling for his release in Hong Kong. Public Domain.

[T]wo hundred lawyers known to defend civic activists by appealing to human rights provisions in the Constitution were placed under detention or house arrest. According to Freedom House, a number simply “disappeared.”

The strike gained online support. Students, intellectuals and artists organized anti-censorship street demonstrations. Similar incidents played out at other newspapers. Officials responded quickly, issuing guidelines further restricting the topics that could be covered by media. According to Freedom House, the guidelines tightened controls on use of foreign sources and domestic blogs. They also introduced a new ideological exam for Chinese journalists to pass in order to receive their press accreditation.

The authorities then arrested New Citizens Movement activists. One leading member was sentenced to 5 years’ imprisonment for “inciting subversion of state power.” Two years later, in July 2015, two hundred lawyers known to defend civic activists by appealing to human rights provisions in the Constitution were placed under detention or house arrest. According to Freedom House, a number simply “disappeared.”

Current Issues

In October 2022, the 20th Party Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) anointed Xi Jinping to a third term as general secretary, breaking an informal two-term limit set by Chinese party leadership in the post-Mao era. This followed years of consolidation of Xi’s control over the party-state apparatus through “anti-corruption” campaigns that successfully purged key rivals and placed loyalists in top party and state positions (see above).

At the 20th Party Congress, Xi publicly humiliated his immediate predecessor, Hu Jintao, by having him removed from proceedings. He then had any persons appointed by Hu removed from the Politburo Standing Committee and the larger Central Executive Commission, the party’s highest leadership structures that direct state policy.

In March 2023, the 14th National People’s Congress unanimously “elected” Xi to his third term as state chairman, or president, of the People’s Republic of China. (The People’s Congress is the nominal state legislature. There are no competitive elections and representatives are all high officials of the Communist Party.) Xi was also appointed chairman of the Central Military Commission, thus continuing the practice of amassing the troika of positions first established by Mao Zedong for a paramount leader.

In October 2022, the 20th Party Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) anointed Xi Jinping to a third term as general secretary, breaking an informal two-term limit set by Chinese party leadership in the post-Mao era.

Xi’s control was reflected in the government’s response to Covid 19. Independent information from Wuhan, the center of the outbreak starting in December 2019, was censored. Doctors seeking to alert the public about the worldwide danger were silenced (see Resources). So, too, was criticism of the government’s handling of the crisis. Zhang Zhan, a citizen journalist, was sentenced to 4 years’ imprisonment for her accurate reports from Wuhan. The government then limited international investigations on the virus’s origins, making it impossible to determine if the virus emerged through zoonotic (animal-to-human) transmission or from a leak from a Wuhan laboratory.

While authorities masked Covid 19’s impact, President Xi directed a “zero Covid policy” through draconian lockdowns. These were enforced by state security forces using China’s high-technology surveillance citizen monitoring system. The full extent of its capabilities to control citizens’ behavior were revealed with omnipresent facial recognition and comprehensive internet and mobile phone monitoring of all Covid 19 test results.

Xi Jinping has been paramount leader, combining all senior state, party and military positions, since 2013. Xi has instituted increasing repressive and surveillance measures to control Chinese society. Shown here in 2016 with Russian president Vladimir Putin, with whom he has established a “no limits partnership.” Shutterstock. Photo by Plavi101.

In November 2023, citizens frustrated by “zero Covid” policies took part in mass demonstrations throughout China following a report of someone who died in a fire because of being locked in at a facility. Protests displayed opposition not just to zero-Covid policies but also to the regime generally. While police suppressed the demonstrations, the largest since 1989, the government eased the “zero Covid” policies in a rare response to public pressure.

The government used the pandemic to tighten further its control over media and the internet. Regulations were issued against dissemination of any news put forward by unregistered journalists, thus barring citizen journalism or even commentary on the internet. Meanwhile, “Great Firewall” censors now remove posts of accurate economic news reporting on China’s sluggish economy and on continued poverty among migrant workers.

The government used the pandemic to tighten further its control over media and the internet. Regulations were issued against dissemination of any news put forward by unregistered journalists, thus barring citizen journalism or even commentary on the internet.

Previously, Chinese authorities had cracked down on “cybercrime,” which is defined as posting pro-democracy opinions or information on taboo topics. A court ruling expanded prosecutors’ power to charge bloggers for content “threatening to public interest” if posts were viewed by more than 5,000 users or reposted more than 500 times. According to Freedom House, thousands of citizen journalists and bloggers were detained, disappeared or criminally charged in recent years. Thus, the little freedom of expression that had emerged on the internet prior to Xi Jinping has been extinguished.

In both Tibet and Uyghuristan (officially known as the Xinjiang Autonomous Region) repression has intensified (see also History). There was detention of more than one million Uyghurs and other Muslims, with a clear intent to limit birth rates, including by systemic sexual abuse and forced sterilization. All those interned are put to forced labor, “reeducated” in CCP ideology and pressed to abandon cultural and Muslim religious practices. “Surplus rural laborers” in Xinjiang and Tibet are being forcibly relocated. Instruction in Mandarin is now mandatory for all children in both regions; they are forbidden to be taught in their native language. US and other governments designated Chinese government practices as ethnic and cultural genocide.

In Hong Kong, Xi Jinping ordered the adoption of a new National Security Law in 2019 that effectively ended Hong Kong’s separate system and the freedoms of expression, assembly and association that had been allowed under its Basic Law.

In Hong Kong, Xi Jinping ordered the adoption of a new National Security Law in 2019 that effectively ended Hong Kong’s separate system and the freedoms of expression, assembly and association that had been allowed under its Basic Law (see History above). Mass demonstrations were organized in Hong Kong against adoption of the law but were repressed by police force.

Hundreds of the demonstrations and leaders of civic movements and democratic opposition parties were arrested. Forty-seven leaders were charged with violation of the new law: thirty-one pled guilty and fourteen were recently convicted and sentenced to harsh terms of imprisonment (two were acquitted). Many Hong Kong activists have fled the island territory

Also, independent media and book publishers were closed down, including Apple Daily, the largest daily newspaper. Its owner, Jimmy Lai, was arrested in May 2020 for encouraging demonstrations against the National Security Law. His trial, begun in December 2023, will likely result in conviction and a heavy sentence.

Mass demonstrations were organized in Hong Kong against the National Security Law but protest organizers and leaders of civic movements and democratic parties were systematically arrested. Creative Commons. Photo by: Studio Incendo.

Xi Jinping’s Hong Kong crackdown and aggressive nationalist rhetoric has led to fears that he may seek to fulfill the “one China” policy by force and invade Taiwan. These fears intensified after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Prior to the invasion, Xi entered a formal alignment with Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin by declaring “no limits” to their countries’ friendship. Since then, China has been careful to not openly violate international sanctions in exports to the Russian Federation, but military and economic cooperation remains high and it is suspected that China’s exports are fueling military production.

Xi Jinping has continued to consolidate his power by replacing both the defense and foreign ministers and intensifying state-party control over “all aspects of life and governance” according to the Freedom in the World 2024 China Country Report. Xi’s systematic eradication of even the smallest level of independent civic activity, academic freedom and free expression resembles more and more the totalitarian practices of the Mao Zedong era. An article in The New York Times is indicative. It reports the reintroduction by Xi of the “Fengqiao experience,” a Maoist system of total surveillance by police and citizens mobilized to ensure adherence to party ideology. Anyone found to be non-adherents should be put through “re-education sessions” (see Resources).

The content on this page was last updated on .